OK, let’s start this post with a little Italian language quiz.

Which one of the following is the correct phrase?

A) Megghiu stàrisi muti e passari ppi fissa, chi parrari e livàri ‘u suspettu. Minchia.

B) Mejo tene’ ‘a bocca chiusa e passa’ pe’ stupido che aprìlla e levà li ddubbi. Ahò!

C) L’è meglio tene’ la bocca ghiusa e passa’ pe’ bischero che aprirla e levare d’ogni dubbio. Deh!

D) È meglio tene’ a vocca chiusa e farese prenne pè fesso che parla’ e scupri’ tutto l’altarino. Uah!

E) Xè mejo tener ‘a boca serada e passar per mona che verserla e cavar ogni dubbio.

I’ll answer this question at the end of the post; but don’t skip and cheat! Read the rest of the post first–who knows, you might learn something (I did when I researched this!)

A Word about Italian Dialects

Officially, Italy has one language which is taught in all schools, both public and private, and these days the literacy rate is an impressive 98%. However, it was not so long ago that a majority of Italians did not speak Italian. In fact, only 2.5% of Italy’s population could speak the standard language when it became a unified nation in 1861.

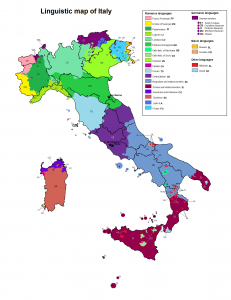

In English, when we mention the word “dialects,” what we are really referring to are merely regional accents with a few minor variations in vocabulary. In Italian, however, “dialetti” are actually separate languages, which contain different vocabularies, different accents, and even different grammar rules. It’s not uncommon in some areas of Italy to find small villages only 10-15 miles apart with remarkably dissimilar dialects—to the point where folks of the older generation can’t communicate with the people from a neighboring village. Compare that to the United States where someone from Washington D.C. and someone from Seattle, Washington (2,800 miles apart!) speak the exact same language.

Because of mandatory schooling, the number of people with the ability to read increased during the post-war era of prosperity and many Italians added the national language to go along with their native dialect. But as recent as fifty years ago, Standard Italian was still a second language for many people (if they spoke it at all), although the trend has since reversed and most Italians are now fully “bilingual.” A greater concern for the future is that many of the more obscure Italian dialects will be lost in subsequent generations. The various forms of media—such as the Internet and Sky TV—are now spreading foreign languages (namely English) throughout the country. Consequently, there has been an influx of many English words and phrases into the everyday Italian, either by direct usage, or by “Italianizing” the words. (Even if you don’t speak Italian, I’m sure you could guess what “downloadare” means!)

Evolution of the Standard Language

Some of the earliest popular documents, which were produced in the10th century, were written in volgare (a “street” version of Latin) rather than proper Latin—in other words, in “dialect.” During the next three centuries, Italian writers wrote in their native dialects, which resulted in the development of several competing regional schools of literature. The year 1230 marked the beginning of the Sicilian School and of a literature showing more uniform traits. Its importance lies more in the language (a move towards a standard Italian) than its subject—a love sonnet style, partly modeled on the Provençal poetry imported to southern Italy by the Normans and the Svevi under Frederick II of Sicily.

It was in the 14th century that the Tuscan dialect became more predominant. This could be due, at least in part, to the central position of Tuscany in Italy as well as the aggressive commerce in the city of Florence, which became a crossroads for business in Europe. The Medici family founded a bank that was the largest in Europe during the 15th century. They, in no small part, helped finance the Renaissance that was flourishing in their city at this time, contributing great sums of money for the support of the arts.

The Tuscan dialect deviated very little in the formation of words and sounds from the classical Latin. Consequently, it most closely harmonized with the Italian traditions in the Latin culture. Most of all, Florentine culture produced the three literary giants who best summarized Italian thought and artistic expression of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. These writers were of course Dante, Petrarca, and Boccaccio.

In 1525, Pietro Bembo, a Venetian, set out his proposals for a standardized language and style. His models were Petrarca for poetry and Boccaccio for prose, and the result became the modern classic standard. Therefore, the language of Italian literature was modeled after the Italian spoken in Florence during the 15th and 16th centuries.

The dictionaries and the publications of the Accademia della Crusca, which was created in 1583, were accepted by learned Italians as the authority in all matters of Italian language; a melding of classical purism (Latin, and later Vulgar) and living Tuscan usage was successfully achieved. During the 17th century, the most important literary event did not take place in Florence, however. It was delivered by the Milanese writer Alessandro Manzoni.

With I Promessi Sposi, Manzoni wrote a novel that had some very specific socio-political goals in mind. First published in 1827, it has been called the most famous and widely read novel of the Italian language (final version published in 1842). The relatively recent French revolution was still fresh in everyone’s memory and Manzoni, like so many other Europeans, looked to it for inspiration for changing his own country. But Italy was fragmented during this time and unification still seemed like a daunting task. So he wanted to compose a work that would unite Italians in many ways and across various social, religious, economic, and cultural differences.

However, the biggest obstacle that he had to overcome was the diversity of language throughout the Italian peninsula. Even in Manzoni’s time, the language of Dante was considered the ideal—but not very many people outside of Tuscany spoke it.

Manzoni himself, being from Milan, did not speak the Tuscan dialect perfectly. After writing his original draft, called Fermo e Lucia, he decided to “tuscanize” it by going through the entire manuscript and converting many of the words into Tuscan—including the name of the protagonist who went from the Milanese name Fermo, to the more Tuscan-sounding Renzo.

The overall result, however, was awkward and it sounded forced and unnatural. Therefore he felt that he needed to “sciacquare i panni in Arno;” to wash his clothes (his language) in the Arno river—or in other words, to actually acquire the Tuscan dialect himself by living in Florence and hearing it spoken in the streets every day before completing the final draft of I Promesi Sposi, which we have today.

Finally in the 19th century, the language spoken by educated Tuscans spread and eventually became the language of the new nation of Italy in 1861. But unification was not—and is still not—easy. In the words of Massimo d’Azeglio, “L’Italia è fatta. Restano da fare gli Italiani.” (“We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.”)

Parla come mangi!

In summary, modern Italian has taken a somewhat twisted route to its present incarnation—from the Sicilian School to Dante’s vulgare to Manzoni’s “laundry” to being declared the state language of a new country in which almost nobody spoke it.

So who speaks Standard Italian today? Almost everyone…and no one. Most Italians use varieties along a continuum; from standard Italian to regional Italian to local dialects, according to what is appropriate in a given situation. Their speech patterns have variations in vocabulary and incorporate intonations and accents that are unique and typical to their hometown. Which I find charming and beautiful. After all, who would want to sound like a dictionary? Much better to parlare come mangi (talk like you eat)!

So as you may have guessed, there is not one right answer for the question at the beginning of this post. They are all correct…and all wrong.

It was a trick question because I didn’t even offer the Standard Italian option, which would have been:

“È meglio tenere la bocca chiusa e passare per stupido, che aprirla e togliere ogni dubbio.”

In English: “Better to keep your mouth closed and seem like an idiot, than to open it and remove any doubt.”

However, the contest is precisely this: The first five NON-Italians who can correctly identify all five dialects will win a copy of my eBook. (Vi prego, italiani, non rovinate il gioco!) ALL FIVE answers must be correct and I’ll base the order of responses from the time stamp on the comments and I’ll close the contest 72 hours after posting—or when I have five winners, whichever comes first. In the event of a tie or dispute, the decision of the judges (well, that’s just me) will be final.

There you have it…I await your responses! In bocca al lupo!

Questa posta è bellissima!

Grazie!

Grazie a TE! Sapevi le risposte giuste?

Grazie a TE! Hai indovinato le risposte giuste?

I really enjoyed this post! Here my answers

A is Sicilian

B is Roman

C is Tuscan

D is from Neaples

C is Venetian or FVG (Triestini say it the same)

I would like to know the Friulian version of it…but cannot think of it now 😀 Italian dialects are so different from each other and difficult to understand.

100% correct!! Brava!! Yes, if you know how to say this phrase in other dialects, please share it!!

Thanks for this post! I don’t think many Americans realize the actual meaning of ‘dialect’ outside the US, or at least in Europe. The Tuscan one….seems more Livornese to me. giusto? non si usa tanto a Firenze.

I meant “deh” non si usa tanto a FI.

You’re right about the Tuscan dialect…I received an email from a reader from Livorno that confirmed it! And yes, “dialect” means something much different in Europe than in the US.

A is Sicilian – Minchia is the giveaway.

B is Roman

C is Tuscan – giveaway is bischero

D is from Campania

E no poderia esare altro che Veneto!

But I live in Italy, so I guess whoever wants a book can be the first one to reply to this comment or something like that.

Right you are, David! Actually, you’re the #4 non-Italian to get it right–I received 3 others via email. But you definitely qualify, because, to be honest, any non-Italian outside of Italy probably wouldn’t know these without a lot of help from a friend or at least google. Fun stuff, though, I find the dialects fascinating. My wife is always trying to teach them to me, but I have a hard enough time with Standard Italian!

Ooops… only now did I read that: “vi prego, italiani, non rovinate il gioco!”.

I’m soo sorry! 🙂

B) is definitely Roman, although there are a few mistakes here and there. The correct version should read: “Ahó, è mejo tené â bbocca chiusa e ppassà pe stupido che aprilla e llevà li dubbi”.

Anyway, I find that the Roman dialect (which should NEVER be called “romanesco” or “romanaccio”… to a local these terms are mildly offensive) is, nowadays, not even a true dialect – it’s more like an accent, a way of speaking.

Thanks for the correction, Marco!

Great post Rick. I think E is Venetian (very similar to my dialect from Trieste) and perhaps A is Sicilian – the rest I don’t know. The whole discussion about dialects is fascinating as my family still speaks the Triestine dialect here in Australia among friends (albeit with an Australian inflexion). By the way, are you aware of International Mother Language Day: it falls each year on 21 Feb. Here’s info: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Mother_Language_Day

Grazie! Yep, you’re right about E and A! I love the dialects, too, because it’s just so interesting how different the language can be across small geographical distances. As I mentioned in the post, it will be a shame when some of the small ones disappear one day. And thanks for the link…I’m going to check it out! Ciao!

B is correct.

Uh-Oh! You fell for the trick…read all the way down to the end of the post!!

Interesting, but I think the concept of “diglossia” should be introduced when dealing with languages in Europe and elsewhere. It is a feature of language where the standard of the language and the variety differ so much ( for various and often historical reasons ) that they are unintelligible to the native speaker

( not the foreigner). Diglossia has been a feature Romance languages in Italy and France as well as Spain as well as other families of the Indo-European languages, German to this day a case in point. Public education and the media have reduced this feature. Then there is the question as to what is a dialect and what is a regional difference. US English for obvious political reasons , while it has regional varieties, does not have dioglossic features.

Hi Sabine, thanks for expanding on the topic and defining dioglossia. Italy is particularly interesting in this phenomenon, and I’m always amazed how diverse the languages can be. Did you know that there (1 or 2) villages in the south of Italy (Calabria) that still speak Old Greek, which hasn’t been used in Greece since the Middle Ages? Unbelievable!