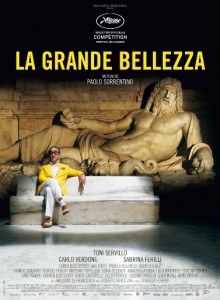

I finally had a chance to see the movie that everyone is talking about. No, not X-Men 9: Why Won’t These Bastards Just Die, but rather Paolo Sorrentino’s evocative portrait of Rome, La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty).

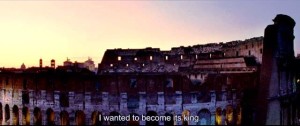

For those who haven’t yet seen this film, it should be noted that, while visually stunning, it is thin on story—which to me is a welcome relief from the aforementioned endless Hollywood blockbuster sequels. Rather, this movie creates a palpable mood and introduces us to some interesting characters…not the least of which is the city of Rome itself. We follow the protagonist, the aging writer Jep Gambardella, through his extraordinary life of rooftop parties and casual encounters, all the while surrounded and seduced by the Great Beauty of the Eternal City.

For those who haven’t yet seen this film, it should be noted that, while visually stunning, it is thin on story—which to me is a welcome relief from the aforementioned endless Hollywood blockbuster sequels. Rather, this movie creates a palpable mood and introduces us to some interesting characters…not the least of which is the city of Rome itself. We follow the protagonist, the aging writer Jep Gambardella, through his extraordinary life of rooftop parties and casual encounters, all the while surrounded and seduced by the Great Beauty of the Eternal City.

Many critics have called it “a Technicolor La Dolce Vita for the Berlusconi era,” which for some reason the director, Paolo Sorrentino, has been keen to denounce. However, the similarities are just too close to Fellini’s masterpiece for even Mr. Sorrentino to completely deny. In fact, he told the press that the two movies have very little in common “except for the setting, their protagonists and their thematic symbolism.” (But that’s almost everything, isn’t it?)

Any foreigner with a genuine interest in Italian culture would do well to study the evolution of Italian film from neorealism to the present day. I recently had the privilege to do just that, watching (and re-watching) several important films under the tutelage of my friend and professor Dr. Ilaria Serra. I learned a great deal, not only about the art of filmmaking, but more pertinent to my interests, a deeper understanding of modern Italian society as it has progressed from the post-war era to today.

The Roots of Neorealism

Neorealism was more an artistic movement than a defined genre. And while the expression of this style varied from director to director (and even within the oeuvre of a given filmmaker), there are certain elements that can be viewed as more or less consistent throughout this early period of Italian cinema.

Classically, we define neorealism as using real people (i.e. non-professional actors) in day to day situations. Even the sets were real—in the city streets and inside actual buildings rather than a recreated reality on a sound stage. Furthermore, they tended to keep the language of the people in the streets, preferring to maintain the dialects and accents of the characters. The result was supposed to give an almost documentary feel to the final work.

In theory, the camerawork and editing should have been totally unobtrusive, but of course this was a myth. Directors couldn’t help manipulating the camera to achiever their final artistic vision. Typically the protagonist was a normal, working class man (or woman) in real life predicaments, thereby allowing the audience to see themselves in the characters and their human experience—a shared destiny. The viewer becomes involved and loses his/her innocence.

But neorealism has few absolutes. The movement was very much a result of timing rather than a conscious artistic method. It was heavily influenced by the anti-Fascism that marked the postwar period. Solidarity was an important theme, along with an implicit criticism of the status quo. Plot and story came about organically from these episodes and often turned on small details. Despite the rather short run (1943 to 1952) the most important films of the period, and the principles that guided them, put Italian cinema on the map and continue to shape contemporary global filmmaking to this day.

Fellini

Then there’s the mythical director himself, Federico Fellini. While he certainly began his career during the neorealism movement—writing screenplays for his mentor Roberto Rossellini—his own films can be seen as a progressive march away from this style. Indeed, you could pick three of his most popular films and chronicle this evolution very nicely. If you’re interested in understanding Fellini, watch these three:

La Strada (1954) still retains some elements of neorealism, but also gives us a few peeks at the style that we will later describe as “Fellinesque.” (How cool to have an adjective in your name become part of the global lexicon?!?). It stars Anthony Quinn as Zampanò, a circus strongman who takes on an apprentice in Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina, Fellini’s real life spouse). These visual elements of circuses, clowns, dreams, carnivals, and parades became trademarks of Fellini. And the sea. Most of his films began and ended at the sea, an homage to his hometown of Rimini.

The ultimate expression of his famous style is seen in the surreal film 8 ½ (1963). The whole movie feels like we’re actually watching one of Fellini’s black and white dreams. In the opening scene we see a man floating above the beach, a rope tied around his foot connects him to the Earth below, and someone is holding the other end, like a flying a kite. We hear only the wind and the man’s breathing. Then he unties himself from the rope and tumbles down towards the sea. And from there it gets weird.

But the inflection point, the film that changed it all for Fellini and indeed cinema in general, is of course La Dolce Vita (1960).

The Not-so Dolce Vita

Ah, yes, that iconic phrase that Fellini made famous with his 1960 masterpiece. However, anyone who has actually watched that film realizes that Fellini was being ironic, if not outright sarcastic. I recently re-watched La Dolce Vita after having seen it about 15 years ago—in other words, before I had ever been to Italy. What I saw the second time was a completely different movie than I remembered. For example, the legendary scene of Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni splashing around Trevi’s Fountain was actually a brief, fairly insignificant moment in the film. And yet that’s what we all remember about the movie.

So the title is actually a contradiction. He was commenting on a “sweet life,” that everyone thought they wanted, but was always just out of reach, largely inhibited by their inability to communicate with one another. The film gives us this glimpse of Italian society as it transitioned from the post-war period of recovery into the era of prosperity and economic growth where the working class begins to have access to modern comforts. Now they have time to “be bored” and to contemplate larger existential questions instead of just concentrating on day to day survival.

Abandoning traditional plot and conventional character development, Fellini creates a cinematic narrative that rejects continuity, explanations, and narrative flow in favor of seven non-linear encounters between Marcello and a cast of minor, often odd, characters. These little “subplots,” if you can call them that, shine a light on the disparity between the life that Marcello imagines and wants, versus what it actually is. He desires connection, but has no idea how to obtain it—he only senses that something is missing in his life. He resorts to pursuing the easy route through endless parties and sexual relations, but ultimately fails in satisfying his desires. (Sound familiar, Mr. Sorrentino?)

In other words, perhaps Fellini is suggesting that endless opportunities, access to modern conveniences, and the freedom to direct every aspect of our own lives has its pitfalls, too. Are we really “better off” in this modern world? The question might be even more pertinent today.

Everybody is talking, but nobody is saying anything

The consumer society critiqued in the Rome of La Dolce Vita looks almost quaint when compared to the incommunicability, voyeurism, and spiritual poverty characterize by today’s chaos of social media existence. If technological distraction and pop-culture idolization leads to a breakdown of real human connections, then Fellini would be incredulous over our present state of society which, not ironically, is heavily influenced by the word “paparazzi” that he coined in this film (the photographer friend of Marcello was named “Paparazzo”).

So what about il maestro himself? Was he able to communicate with his audience? Fellini, a self-confessed “honest” liar, said about his own films, “I don’t understand them either. I don’t seem capable of even suggesting an interpretation.”

But this too is a lie. Because although he may not have had the words to explain his messages, he communicated a great deal through the medium that he helped define by using a cinematic narrative which rejected conventional explanations and narrative logic in favor of his own brand of communication, which by-passed the intellect in favor of speaking directly to our shared emotions through visual and thematic symbolism.

The Great Beauty of Rome

Back to this year’s Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Film, The Great Beauty. The director, Mr. Sorrentino, told the New York Times:

Back to this year’s Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Film, The Great Beauty. The director, Mr. Sorrentino, told the New York Times:

“In Rome today, since it’s hard to be optimistic, there’s a kind of lassitude that found its symbolic culmination in dancing, in conga lines, in trying to seduce the beautiful woman of the moment or the beautiful man of the moment. It seemed that this has become the principal occupation of the country.”

The Roman rooftop terrace parties in The Great Beauty show a culture that is blocked, resigned, embalmed in elegant decline, where some seek religion and others cocaine, and intellectuals talk endlessly about what’s wrong and yet inertia overwhelms all forward momentum.”

Here we go again, Fellini redux: incommunicability. People are speaking, but nobody is really communicating…they’re merely looking for a quick fix, or a distraction from the unstoppable social decay. This is especially true in Rome, perhaps, where the political elite with their golden parachutes and blue cars are still pretending that nothing much is wrong. As the director says, “There’s a sense that the nerve centers of the country had fallen asleep on their couches. And so I tried to turn that into a film — that everything had become a bit of a salon.”

And he did so very successfully, according to most critics. So I’m sorry to disappoint you, Mr. Sorrentino, but I think Fellini would have been impressed with your work. Maybe even flattered by the comparison.

For further reading, check out this fine article on The Paris Review: Lost in Translation

Great piece with some very cool insights! Just out of curiosity, where did you get the impression that Sorrentino was trying to distance himself from Fellini? I’ve gotten the opposite feel.

Here’s a quote from Sorrentino that was included in the press notes for the film: “Of course, Roma and La dolce vita are works that you cannot pretend to ignore when you take on a film like the one I wanted to make. They are two masterpieces, and the golden rule is that masterpieces should be watched but not imitated. I tried to stick to that. But it’s also true that masterpieces transform the way we feel and perceive things. They condition us, despite ourselves. So I can’t deny that those films are indelibly stamped on me and may have guided my film. I just hope they guided me in the right direction.”

Grazie! My Italian film professor said as much from the feedback she’s read. Plus I’ve read a few of his comments myself (translated) that suggest he doesn’t like the comparison…EITHER out of being humble, or perhaps he’s concerned that his film won’t measure up in the shadow of Fellini.

But I think the quote that you’ve cited speaks more directly to the point: the influence of films like “Roma citta’ aperta,” and “La Dolce Vita,” can’t be avoided in any case. For any Italian filmmaker, those films are always lurking in the subconscious.

P.S. I hope that people will click over to your review for a much more complete and in-depth analysis.

http://www.vivaitalianmovies.com/post/66746560197/great-beauty-movie-review#.UtwXVxAo7IU

Yes Rick,another tour the force!Your explanation of “”NEOREALISM”” is definitely grand,and i am sure it must have satisfied most of your readers.Alla prossima…….buon lavoro…………PINO

Fantastic post! Now I need to re-watch some Fellini and Paosolini.

Thanks, Gillian! Yes, it becomes so interesting to rewatch these films with the historical background in mind. Ciao!

For some reason, this website loads slowly! But I really enjoy your content.

Grazie, Alonzo! Yes, that happens sometimes…I’ve been thinking about changing my host. 🙁

Haha, the two movies have very little in common “except for the setting, their protagonists and their thematic symbolism.” I heard it won the Golden Globe and have added it to my Watchlist.

Thanks for breaking down Neorealism for me. I recently watched La Dolce Vita and thought that Fellini had to be kidding, had to be sarcastic because the events that played out in Marcello’s life somewhat resembled moments in Miami that I have witnessed during events or known to have happened to others, like my party animal brother. I thought he had to be kidding in the sense that his life did not look that great, his friend committed suicide (after killing his kids, mammamia!), his father had a heart attack (or something) when he went back to the French dancer’s home… looked like a long painful hangover to me. lol. The ending left me confused and definitely needing some closure.

I did appreciate how Fellini “rejects continuity, explanations, and narrative flow” which is probably why I wanted it to run another hour so more things would happen hoping something would connect to something else. This could very well be the OCD in me.

I must be honest I love Mr. Allen, but was not into his “To Rome With Love.” Maybe you can enlighten me on that one too, because I really wanted to like it, although I enjoyed the father that was only able to sing in the shower, however the rest fell flat. It felt like he tried to push sex way to much making it more painful to watch compared to a Fellini moment when things ‘just happen.’

Hi Rick,

I most definitely want to see the new film, but I must admit it will be because I want to see “the great beauty” of my favorite city. Maybe unfortunately I have never wanted to be too knowledgeable about Italian movies though I have watched some I didn’t much care for because I “thought I should.” My favoite has been Roberto Bengnini’s Life is Beautiful. (Sorry, but I’m not sure I have spelled his name correctly or remembered the name of his film correctly.)

I am more of a book lover and have read several of the ones you recommended a while ago. Also have read and watched “The Rape of Europa.”

At present I am reading and enjoying the Hughe’s book. Of course, I am also wading through quite slowly “Rome–the Autobiography” edited by John E. Lewis. This consists of excerpts from actual writings from around 700 BC to around 500 AD, dates give by the author to cover the “rise and fall of the Roman Empire by those who saw it.”

I think I have probably babbled on enough for now!

The book by Lewis sounds really interesting! Might have to add that one to the ever-growing stack!

It is interesting, but it can be slow going because of wordiness and some unfamiliar structure. But it comes mostly in some very short parts so it is easy to stop and do something else